What you need to know about shark nets in South Africa

Header image credit: Josh Pons

Shark nets are just what they sound like: Sprawling underwater barriers designed to remove sharks from public beaches. Unsurprisingly, there is a price for bather protection, and sharks have been paying it for decades.

Shark nets and drumlines have long been used in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa – their presence has been normalised for years as a preventative safety measure for ocean users, but many are unaware of their broader impact on marine ecosystems, ocean health, and the sharks themselves.

In 2023, the Earth Legacy Foundation started a petition calling on the KwaZulu-Natal Sharks Board to remove lethal shark nets and drumlines. The Two Oceans Aquarium has recently come on board as a supporter.

How are shark nets and drumlines currently used?

In the 1940s, a series of shark bite incidents in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) caused public outcry amongst locals and a steep decline in tourism. Following the example set in New South Wales, Australia, the Durban municipality deployed shark nets in 1952. These gillnets were set to catch and remove sharks before they entered public beaches, thus reducing the chance of anyone being bitten.

By the time the KwaZulu-Natal Sharks Board (KZNSB) was established in 1974, shark nets were a ubiquitous presence along the KZN coast. Shark incidents were practically non-existent, and the public felt safer.

However, it quickly became apparent that shark nets do not discriminate, posing a huge risk to other marine life. According to Dr Shanan Atkins, Coordinator at the Indian Ocean Humpback Dolphin Conservation Network, “Shark nets catch anything of a certain size. Besides the three target shark species (bulls, whites, and tigers), the nets catch numerous other large sharks that are not considered targets, like ragged-tooths and hammerheads, and other large animals like dolphins, turtles, and rays.”

The KZNSB took steps to reduce these numbers by introducing drumlines; a euphemism for what are in fact baited hooks suspended from a large, anchored float, as an alternative in 2005. This method lowers the risk of bycatch by targeting large shark species with bait. Obviously, the shark mortality rates with drumlines are still high.

Today, shark nets and drumlines are deployed at 37 of KZN’s beaches. In a continued effort to ease their environmental impact, the KZNSB cut the number of beaches using shark nets from 46 to 37 and reduced net lengths by 70%. The nets are in place for about half the year, except during the annual sardine run from June to November. In this time, when marine life flocks to the feeding frenzy, almost all the shark nets are substituted for baited hooks to reduce bycatch.

Despite these measures, the statistics entangled within the shark nets and baited hooks are damning: “The target sharks make up just 15% of the catches, while only 27% of all the animals that are caught survive. In other words, for every target shark caught, five non-target animals are caught. Most of them die,” said Dr Atkins.

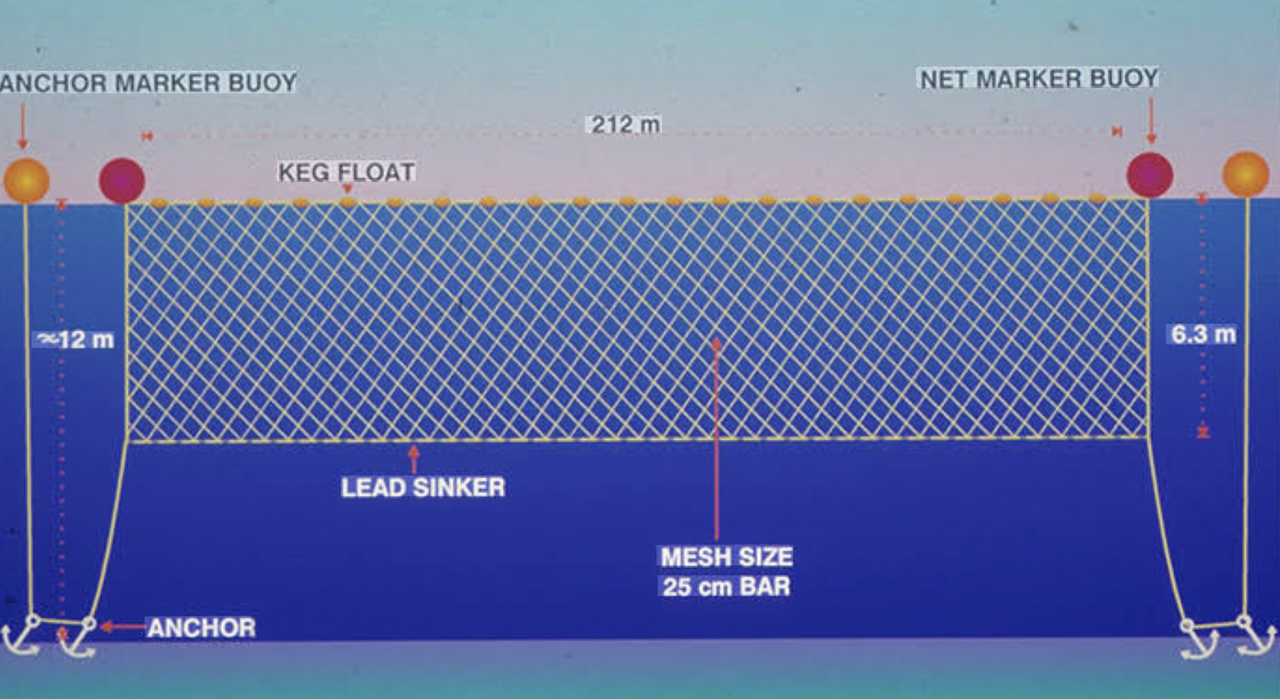

Most of the nets are located approximately 400m offshore at depths of 14m – they are about 214m long and 6m deep, secured on each end by anchors. Interestingly, shark nets do not form a complete barrier all the way to the seafloor – in fact, sharks can swim under or around the ends of nets. This prompts interesting questions into the actual efficacy of shark nets in improving bather safety.

This story, where sharks have harmed humans and humans have reacted by culling sharks (and other marine life indirectly), is a textbook example of a human-wildlife conflict in which the animals come off second-best. Nevertheless, the shark nets remained in place for decades, during which public perception of sharks remained largely fear-based.

Ending the use of lethal shark safety nets

In recent years, the ethical shortcomings of shark nets began to surface as perceptions swung from fear of sharks to breaking misconceptions and raising awareness for their plight.

Following the death of a juvenile white shark in KZN in May 2025, the founders of Earth Legacy Foundation ignited a movement calling for urgent reform of shark safety practices. The need for reform is more pressing than ever: Over the past 70 years, global shark and ray populations have dropped by over 70%. It is also estimated that 11 000 sharks are killed every hour. The need to replace lethal methods with humane, effective alternatives is critical.

The petition calls for immediate trials of non-lethal solutions at five KZN beaches, followed by the phased removal of lethal nets and drumlines if trials succeed. Proven options like SharkSpotters, drone surveillance, and exclusion barriers have the potential to protect both people and marine life. The petition also requires involvement from an independent panel of local conservationists and ocean-users who will manage the transition to humane shark safety systems in partnership with the KZNSB.

This appeal is fully supported by the Two Oceans Aquarium, as it naturally aligns with our vision of a healthy and abundant ocean. “As one of the cornerstones of marine ecosystem health, sharks play a central role in maintaining balance in our ocean and removing them could have devastating knock-on effects. It is time to shift our thinking and employ humane methods to protect sharks and other marine species, not only for their sakes, but for ours too,” said Helen Lockhart, Conservation and Sustainability Manager at the Aquarium.

What are the ecological impacts of shark nets?

The effects of shark nets on our marine ecosystems are far-reaching and profound.

Sharks keep ecosystems in balance

Sharks are unquestionably positioned amongst the apex predators of the ocean. Big or small, sharks are often regarded as keystone species for the essential roles they play in ecosystem health.

This impact is felt in myriad ways. By feeding on middle-tier predators and grazer species, sharks keep these species’ numbers at a sustainable level. This keeps the food chain balanced, preventing overconsumption and food scarcity.

One study highlighted the knock-on effect of sharks being removed from an ecosystem: Without the threat of predation, smaller game fish inundated a coral reef system and significantly reduced the local herbivore populations. These grazer species were vital in regulating algae growth – without them, algae completely smothered the coral reef. Without an apex predator to catalyse the chain reaction of population control, entire ecosystems fall to pieces.

“When you remove sharks, you destabilise food webs, which affects coral reef health, fisheries, and ultimately the resilience of our coastal environments. Shark nets and drumlines make the ocean weaker,” says Esther Jacobs, Earth Legacy Foundation.

Shark nets do not discriminate

Shark nets and drumlines may successfully catch target species, but far too many other marine animals meet their end in these nets. These animals are grouped with the rest of the ocean’s bycatch, which encompasses all non-target species unintentionally caught in fishing gear. While the fishing industry accounts for the majority, shark nets make a notable contribution.

“Shark nets and drumlines are often mistaken for protective barriers. In reality, they are devices designed to kill. Their impact on South Africa’s marine ecosystems is completely indiscriminate. They don’t just target specific sharks; they entangle and kill dolphins, rays, turtles, seabirds, and other threatened species. These deaths disrupt the entire balance of marine life,” says Jacobs.

The Indian Ocean humpback dolphin (Sousa plumbea) is a prime example. This species is listed as Endangered on the IUCN’s Red List, with small, coastal populations and low resilience to increased mortality. In Richard’s Bay, KZN, the dolphins used to experience unusually high bycatch rates in shark nets – in fact, the site was the worst known hotspot for this species’ incidental capture in South Africa. Multiple studies have been conducted in this regional population, recognising that bycatch in shark nets significantly contributed to the dolphins’ overall mortality rate. According to Dr Atkins, these numbers were largely reduced once shark nets were swapped out for baited hooks. Still, this case study illustrates the danger posed by shark nets – an ecologically important species could have become locally extinct.

While the KZNSB has reduced the number of beaches using shark safety measures and decreased net lengths to 13.5km, shark nets still catch more than 500 sharks and other species every year. Even when the nets are taken out in winter, they are replaced by 100 additional baited hooks.

The paradox of shark nets in Marine Protected Areas

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are the “nature reserves of the sea”; spaces dedicated to achieving long-term conservation of the ocean and allowing key marine species to recover and thrive. It is ironic that, of South Africa’s 42 incredible and diverse MPAs, three are permitted by the Department of Forestry, Fisheries, and Environment to employ lethal shark nets. The uThukela, Aliwal Shoal, and Trafalgar MPAs have a combined total of seven installations of shark nets and baited hooks.

Aliwal Shoal and uThukela MPAs are crucial breeding and aggregation habitats for multiple shark species, including ragged-tooth, bull, tiger, and hammerhead sharks. In winter every year, tourism peaks as ragged-tooth sharks migrate to these MPAs to mate, and recreational scuba divers flock to swim alongside the sharks. The presence of shark nets within any MPA is incongruous with their mission as safe havens, but the shark nets within Aliwal Shoal and uThukela MPAs send a disturbing message.

“On one hand, South Africa is investing in ocean protection with MPAs, while on the other, we’re allowing sanctioned killing within those same boundaries. Our government should be quite ashamed of its policies being sabotaged by seriously outdated practices. If we’re sincere about our commitment to ocean health, these lethal measures simply can’t coexist with conservation goals,” says Jacobs.

What are the proposed alternatives to lethal shark nets?

In recent years, the need for alternatives to lethal shark nets has become increasingly clear. Dr Judy Mann-Lang, Head of Strategic Projects at the Two Oceans Aquarium Foundation, and Dr Atkins recently co-authored a research paper that focused on finding ways to reduce the impact on sharks and other marine life without increasing the risk to humans.

The researchers aimed to bridge science, local knowledge, and decision-making around the bather-shark conflict by connecting different stakeholders to explore realistic solutions to protect both people and sharks. The stakeholders identified were those in the tourism and conservation sectors as they are most likely to be professionally engaged in the “bather-shark system”.

The actions proposed by these various stakeholders fell under three themes: Collaborate (mobilise diverse expertise and leadership), re-use (utilise existing knowledge and structures), and weigh up (consider costs and benefits). Some of the most impactful takeaways centred around collaboration for conservation. Participants suggested setting up a transdisciplinary working group to support reducing the ecological impact of KZN’s shark nets, as a diverse group is more likely to produce adaptable and inclusive solutions to the conflict than fact-based approaches alone.

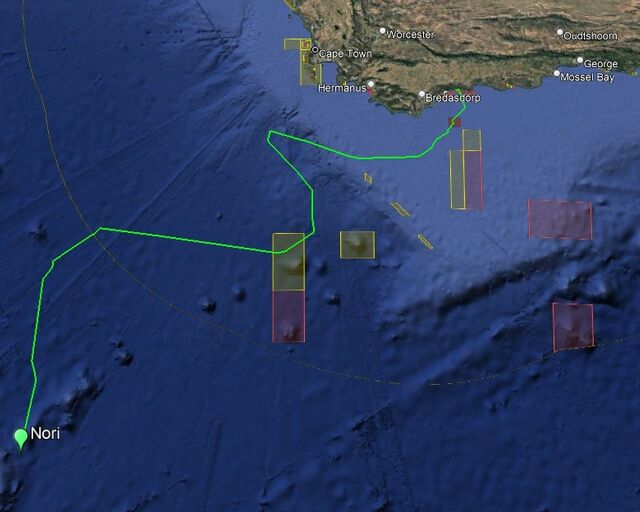

Another community-driven approach would be to identify influential “champions” within the local municipalities who can help drive change. In Cape Town, SharkSpotters is a successful example of community champions in action. Funded by the City of Cape Town, SharkSpotters takes a proactive, humane approach to keeping people and sharks safe. By monitoring shark activity through visual and drone surveillance and alerting beachgoers, Shark Spotters reduces the chance of encounters between people and sharks. The organisation has also been operating a unique shark exclusion net in the Fish Hoek area since 2013. Unlike the nets used in KZN, these exclusion nets have much smaller mesh, so no large sharks can become entangled. The barrier is deployed and retrieved daily and is specially designed to have minimal environmental impact and adapt to changing weather conditions.

SharkSpotters also responds to shark-related emergencies, carries out research on shark behaviour, builds public awareness around shark safety and conservation, and creates jobs and training opportunities for local spotters. While certain aspects of the SharkSpotters model may need to be adapted to KZN’s turbid waters and bottom-swimming shark species, the initiative ought to be tested in a KZN context. With their connection to the community and high success rate with averting bather-shark conflict, SharkSpotters could provide an incredibly effective model for shark safety in KZN.

How can the KwaZulu-Natal Sharks Board lead the transition to non-lethal methods?

According to Jacobs, the KZNSB has a real opportunity to lead the transition toward humane shark safety methods that benefit both humans and sharks.

“The KZNSB holds decades of data, experience, and community trust, all of which could be channelled into developing and deploying world-class non-lethal solutions. Instead of being known for destroying marine biodiversity, they could be known for pioneering coexistence by integrating proven non-lethal methods and ocean education. The science is there, the technology is there, and there is a global shift happening. What’s missing is the Sharks Board’s willingness to stop resisting and to move beyond outdated practices,” she says.

Jacobs predicts that, as the KZNSB has operated under the same culling mandate for decades, shifting to non-lethal methods requires political will, funding, and budget redirection. However, the success stories seen elsewhere prove that coexistence is ecologically and economically more effective, ethical, and sustainable.

For decades, the overwhelming majority were willing to remain oblivious to the impact of shark nets. Today, with global shark populations in sharp decline, it has become distressingly clear that humans are more dangerous to sharks than vice versa.

The campaign to eradicate lethal shark nets and drumlines has gained encouraging momentum on a public level, but the ultimate decision lies in the hands of those holding the nets.

Related News

Sign up to our Newsletter

Receive monthly news, online courses and conservation programmes.