This school holiday, school’s out and sharks are in: We’re diving into the incredible sharks at the Two Oceans Aquarium – big and small.

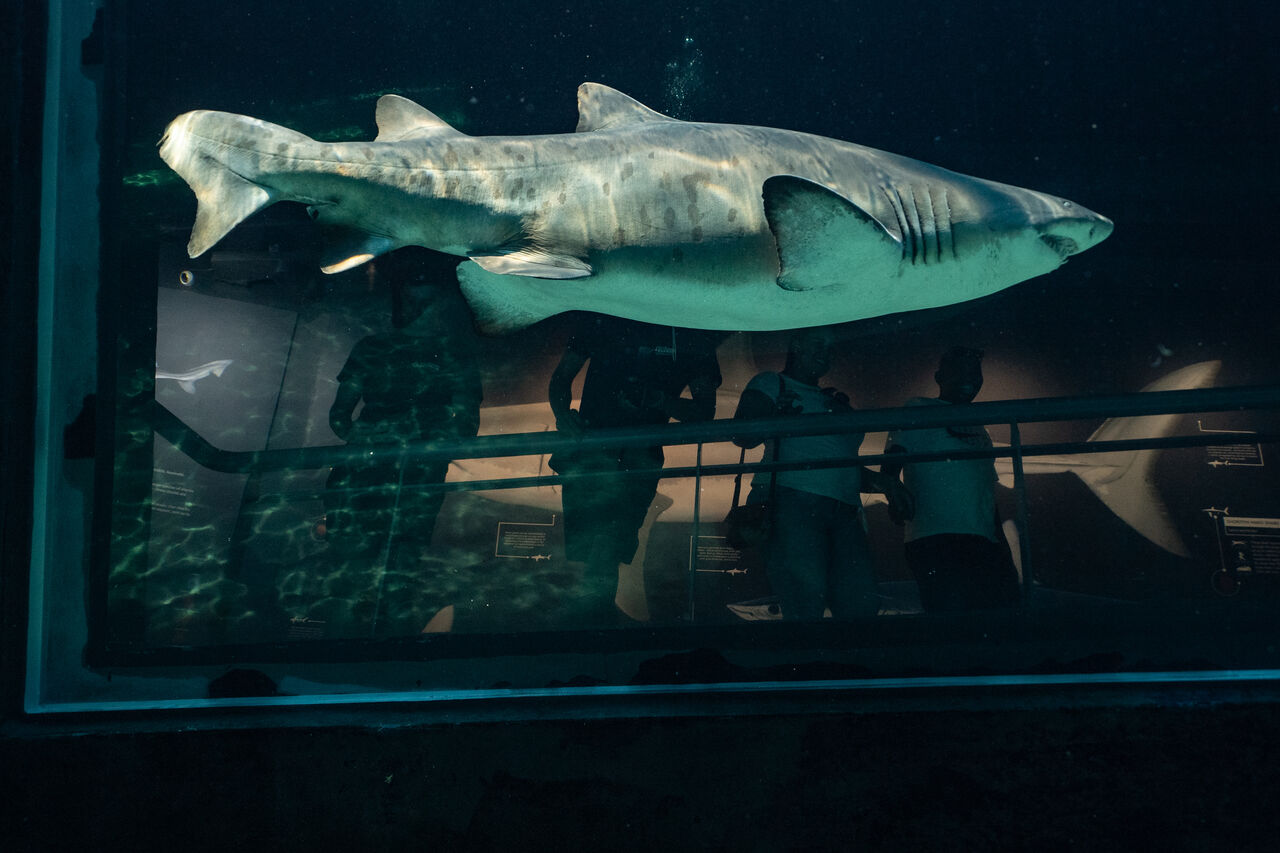

The Aquarium is home to a remarkable variety of shark species, many of them found only in South African waters. From the iconic ragged-tooth sharks cruising through the Save Our Seas Foundation Shark Exhibit to the elusive puffadder shysharks in the Cold Reef Exhibit, visitors are offered a glimpse into the complexity and beauty of these misunderstood animals.

Today, we’re learning all about ragged-tooth sharks.

What are ragged-tooth sharks?

Ragged-tooth sharks (Carcharias taurus) are a particularly fascinating and unique shark species. With their spotty bodies and permanently toothy grin, they certainly have an iconic look within the shark world. At the Aquarium, we fondly call them “raggies”.

Raggies have multiple names around the world: They are known as sand tiger sharks in the US, grey nurse sharks in Australia, and spotted ragged-tooth sharks in South Africa. Despite these differences, these sharks are all the same species: Carcharias taurus.

Raggies are ovoviviparous, which means they give birth to live pups. Unlike mammals, though, they do not have placentas to provide the pups with nutrients. Instead, the pups feed on the yolk of their egg sac until they hatch inside the uterus. Once hatched, they grow even bigger by eating the smaller embryos and unfertilised eggs that they share the space with – this is called intrauterine cannibalism. Finally, after a gestation period of 9 to 12 months, the mother raggie gives birth to two pups. At this point, the pups are about a metre long and completely capable of taking on the ocean!

This reproductive strategy ensures that the ragged-tooth shark pups are as prepared as possible for life in the ocean before they are born, but the process is very slow, and offspring are produced at a low rate. As adults, raggies can reach lengths of about 3.5m and live for nearly 30 years.

Raggies are long-distance swimmers

Raggies are slow-moving sharks – they spend most of their time near underwater caves, gullies, and rocky or coral reefs in tropical and temperate seas, mainly in shallower waters of up to 25m deep.

While they live relatively relaxed lifestyles, their yearly migration is no mean feat. Every year in winter, ragged-tooth sharks move to the cool waters of the southern Cape to give birth. When summer arrives, they migrate to the warmer waters of KwaZulu-Natal and Mozambique to mate. That’s a journey of about 3 000km every year!

They have a special buoyancy technique

Most fish use a gas-filled swim bladder to adjust their buoyancy so that they can more effortlessly maintain a certain level in the water column. Most sharks do this differently – their lightweight cartilage skeletons and large, oily livers lower their density, so they don’t need swim bladders.

Ragged-tooth sharks take their commitment to being unique even further – they swim to the surface and swallow air bubbles to adjust their buoyancy. If they accidentally swallow too much air, they just burp it up!

Raggies are skilled hunters

Ragged-tooth sharks’ slow movements and efficient buoyancy control make them the perfect stealth hunters. During the day, they lay low in the shadows of the shallow waters. They leave their shelters at night and, skimming close to the seafloor, roam long distances in search of prey like bony fish, skates, and small sharks. Typically, this hunting behaviour is solitary, but raggies have been known to coordinate hunting in groups in areas where large schools of fish are present.

As many of our Two Oceans Aquarium visitors have no doubt noticed, raggies have mouths full of pointy, needle-like teeth. These are great for gripping onto slippery fish but are not very good at biting off pieces of food – that’s why we see the sharks shaking their heads to try to reposition their food to be swallowed whole.

Are they endangered?

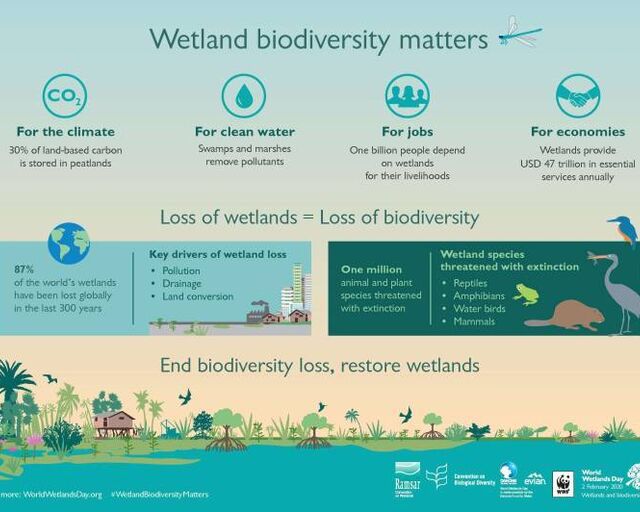

Ragged-tooth sharks are listed as critically endangered on the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species. One of the main reasons for this is fishing pressure, as raggies are captured both as target and bycatch in artisanal, recreational, and industrial fisheries. The threats of entanglement in ghost fishing gear and shark nets are also contributing factors to their decline. Their slow rates of reproduction greatly reduce the raggies’ ability to withstand this pressure.

Raggies are also threatened by habitat loss and degradation. As their preference is for coastal inshore waters, they are more vulnerable to the effects of urban development, such as runoff, pollution, and reef degradation.

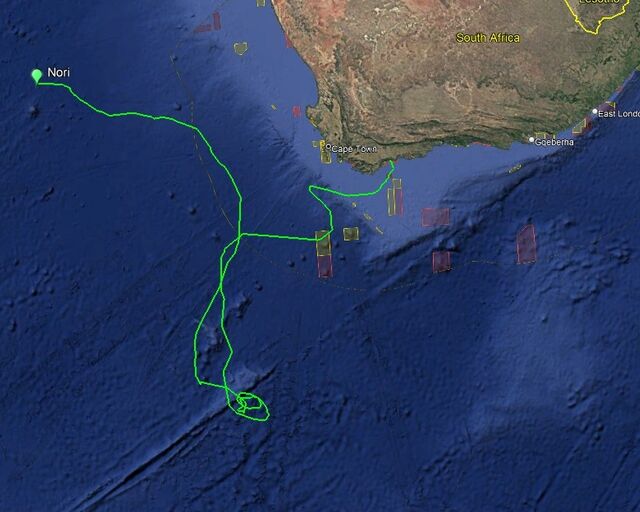

The ragged-tooth sharks at the Two Oceans Aquarium are incredible ocean science ambassadors for their critically endangered species. Since 2004, every time the Two Oceans Aquarium releases a shark, it is fitted with tagging devices that allow it to be tracked and monitored. These efforts have supported the work of many conservation science organisations. The Aquarium's ragged-tooth sharks have revealed their South African migration pattern, their preferred resting sites, and confirmed that sharks kept at the Aquarium for short periods have been able to return to their normal, natural behaviours once they return to the wild.

Ragged-tooth sharks, both in the Aquarium and out, are wonderful examples of the biodiversity and beauty that lies beneath the waves. You can marvel at the raggies as they glide through the Save Our Seas Foundation Shark Exhibit or watch as they get fed on Saturdays at 12h00.

Related News

Sign up to our Newsletter

Receive monthly news, online courses and conservation programmes.