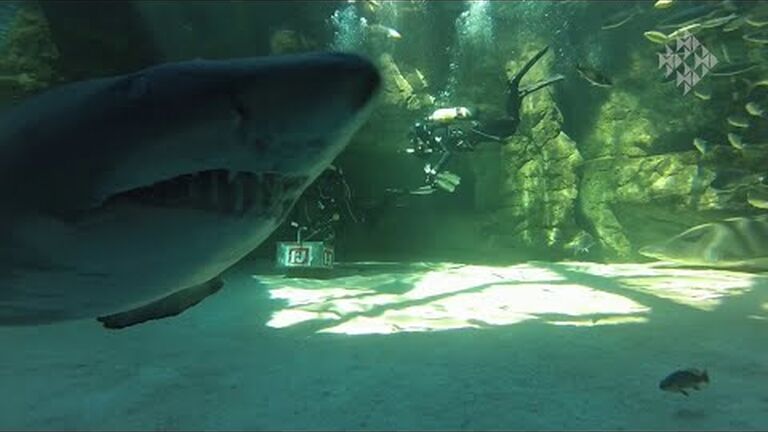

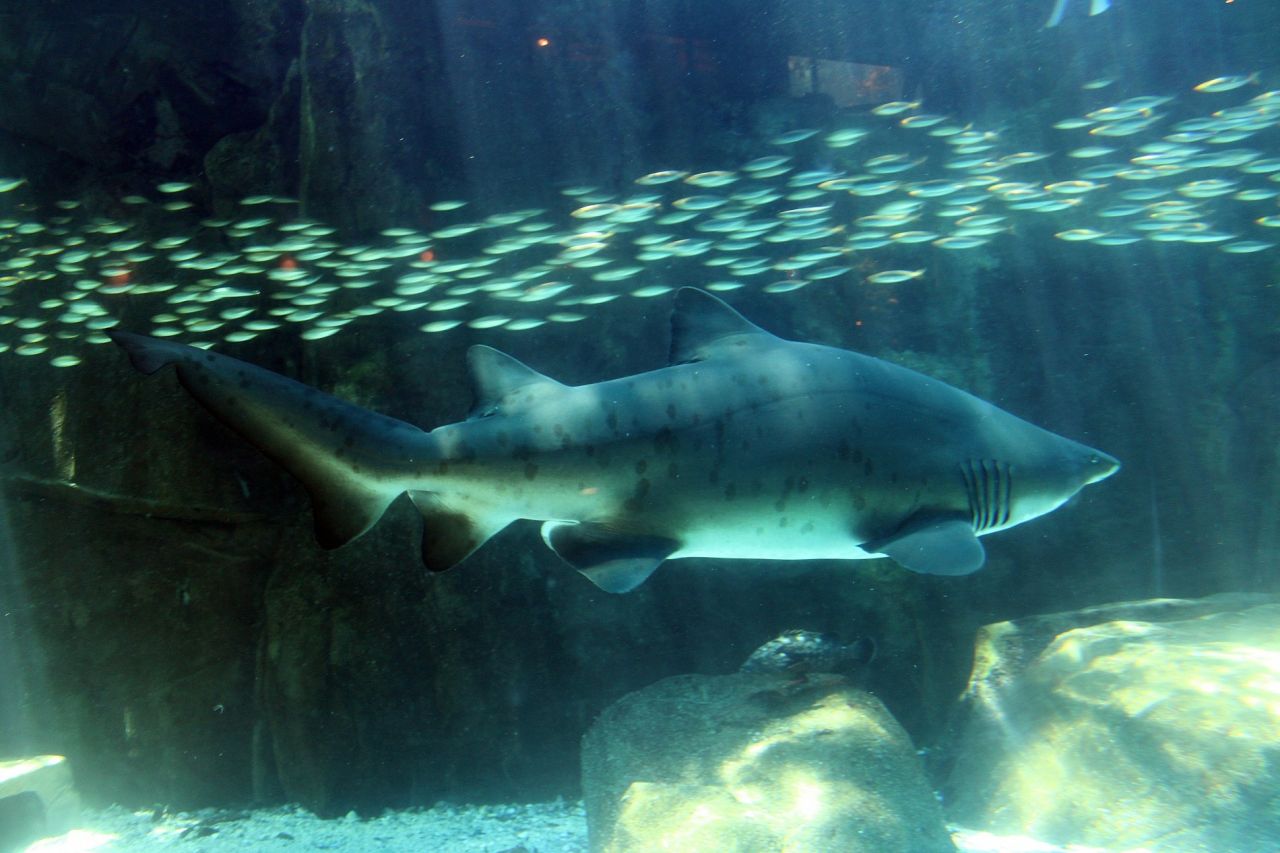

When you visit the Two Oceans Aquarium, one species always stands out as a highlight. For many people it is the ragged-tooth sharks of the Save Our Seas Foundation Shark Exhibit. These large sharks are not just an icon of the Aquarium but are one of South Africa's most easily recognisable sea animals. They are also one of the most well-known sharks globally, and for good reason: Ragged-tooth sharks are (j)awesome!

Spotted ragged-tooth sharks, also known as grey nurse sharks and sand tiger sharks internationally (more on that later), occur in temperate to tropical coastal waters of the Atlantic, Indian and western Pacific oceans. In South Africa they are common along the eastern and southern coasts, occurring as far west as False Bay.

"Raggies" as they are affectionately known locally, are large sharks, that can reach up to 3.5m in length. They have a characteristically bulky body and pointy snout, a build that allows them to be sleek enough to move stealthily, but also be muscular enough to very quickly snap at large prey, which includes other sharks. Their jagged, narrow teeth are well adapted for gripping slippery prey, like large squids and fish, but they lack the ability to cut through their prey, so larger marine mammals are not on their menu.

Shark life

Ragged-tooth sharks are nocturnal hunters. During the day they rest in sheltered rocky shallows, but at night they move into the open, staying low and often travelling long distances from their resting spots. Although usually solitary, ragged-tooth sharks will often congregate and work together to hunt schools of fish. Overall, the cautious lifestyle of the ragged-tooth shark makes it an excellent nocturnal predator that can thrive in water inhabited by competing large shark species.

Raggies have a special buoyancy strategy not available to any other type of shark - they can gulp air at the surface and use the air bubbles in their stomachs to maintain neutral buoyancy. This allows them to glide almost effortlessly through the water, making minimal noise or detectable vibrations, easily making them one of the stealthiest large shark species. Using this approach, they will glide quietly past their prey, typically large fish, rays or smaller sharks, like spotted gulley sharks, and with a quick sideways swipe of their heads, grab their prey as they pass.

Ragged-tooth sharks have fairly violent mating behaviour, as the females are often badly bitten. The reason for this is that the males have to latch onto the females during copulation and they have only their (tooth-filled) mouths to do so!

It really is a shark-eat-shark world, and ragged-tooth sharks have evolved to give their pups every possible opportunity to survive. This apparently violent mating ritual allows fertilisation to take place internally. Female ragged-tooth sharks each have two uterine horns containing about 50 fertile eggs at any time, and it's quite possible that different eggs can be fertilised by different male sharks when mating occurs.

Instead of laying these eggs, the shark embryos develop inside the mother. The largest embryo in each horn will eat all the other embryos, a process called intrauterine cannibalism. Once all other embryos have been consumed, the surviving embryo will feed off of the yolk of a constant supply of unfertilised eggs supplied by the mother. After an eight to twelve month gestation, the female will give birth to one or two fully-developed offspring that are already over a metre long and able to immediately fend for themselves.

Their large size, combined with the southward migration of the pregnant mothers, give juvenile ragged-tooth sharks an excellent start to life, as they can already outcompete many smaller shark species, and at the same time do not present as competition to adult raggies. Their slow growth rate, and low reproductive rate, make the survival of each juvenile into adulthood absolutely vital for the survival of the species in general.

What's their name actually?

"Spotted ragged-tooth shark" is the South African common name for this shark, but this name isn't actually used outside of southern Africa. Locally, ragged-tooth sharks are usually referred to by their affectionate nickname - "raggies".

In the US, and most of the world, they are called "sand tiger sharks" - a name that is terribly ambiguous as it confuses the ragged-tooth shark with three other species: The Indian sand tiger shark (Charcharias tricuspidatus), the small-toothed sand tiger shark (Odontaspis ferox) and the big-eyed sand tiger shark (Odontapis noronhai). The name also leads to this shark being confused with the tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier).

In the UK and Australia they are called grey nurse sharks and in India they are known as blue-nurse sand tigers - also both highly ambiguous, as ragged-tooth sharks are not related to nurse sharks.

Its non-English names (which are not direct translations of its English names) are equally confusing. In German, it is a schnauzenhai (snouted shark). In Arabic, it is kalb, and in Indonesian it is a hui anjing - meaning "dog", "dog shark" or "dogfish". In Finnish it is a heitahai (white shark) and in Japanese, it is shirowani (white sea dragon) - names that also apply to the great white shark.

And, even their binomial name Carcharias taurus is a bit of a misnomer, translating to "bull shark" - ragged-tooth sharks aren't bull sharks either.

So, although South Africans might be the only ones to use the name "ragged-tooth shark", we have definitely chosen the most appropriate name of the lot!

Shark ambassadors

All the ragged-tooth sharks housed in the Two Oceans Aquarium, including the large specimens seen in the Save Our Seas Foundation Shark Exhibit, are, in fact, juveniles and in most cases are actually females. After spending a few months or years at the Aquarium, these sharks are returned to the wild, usually in the vicinity of Buffels Bay on the Garden Route, with care being taken to do so at the time of year when ragged-tooth sharks of a similar age and size are in that area too.

Prior to their release, our sharks are fitted with tags that allow them to be tracked as they move along our coastline. These tags have allowed researchers to confirm that sharks kept in captivity and released back into the wild are able to return to their normal, natural behaviours, and have also contributed to research that revealed the unique ragged-tooth shark migration patterns discussed earlier.

Ragged-tooth sharks are a species commonly kept in aquariums globally, owing to the fact that despite being large and "toothy", they are a relatively docile species. They are also one of the largest species of shark that are not obligate ram ventilators, which means that they do not need to keep swimming in order to breathe. This makes them a bit easier to work with and care for in an aquarium environment.

Although ragged-tooth sharks have a fearsome reputation, owing to their protruding teeth, they are a relatively shy species and incidents involving humans are exceedingly rare. In fact, there are no recorded human deaths associated with ragged-tooth sharks, and very few incidences of unprovoked attacks.

Conservation status

Due to their slow growth rates, low fecundity (ability to produce many offspring) and high age of maturity, ragged-tooth sharks struggle to overcome the damage caused by overfishing. This danger was identified in 1984, when ragged-tooth sharks in Australia became the first shark species to receive protection anywhere in the world, and other countries, including South Africa, have since followed this example. Ragged-tooth sharks are listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, and are in fact Critically Endangered in the Mediterranean and the seas surrounding Europe.

Related News

Sign up to our Newsletter

Receive monthly news, online courses and conservation programmes.