The sardine run is underway, but where have all the fish gone?

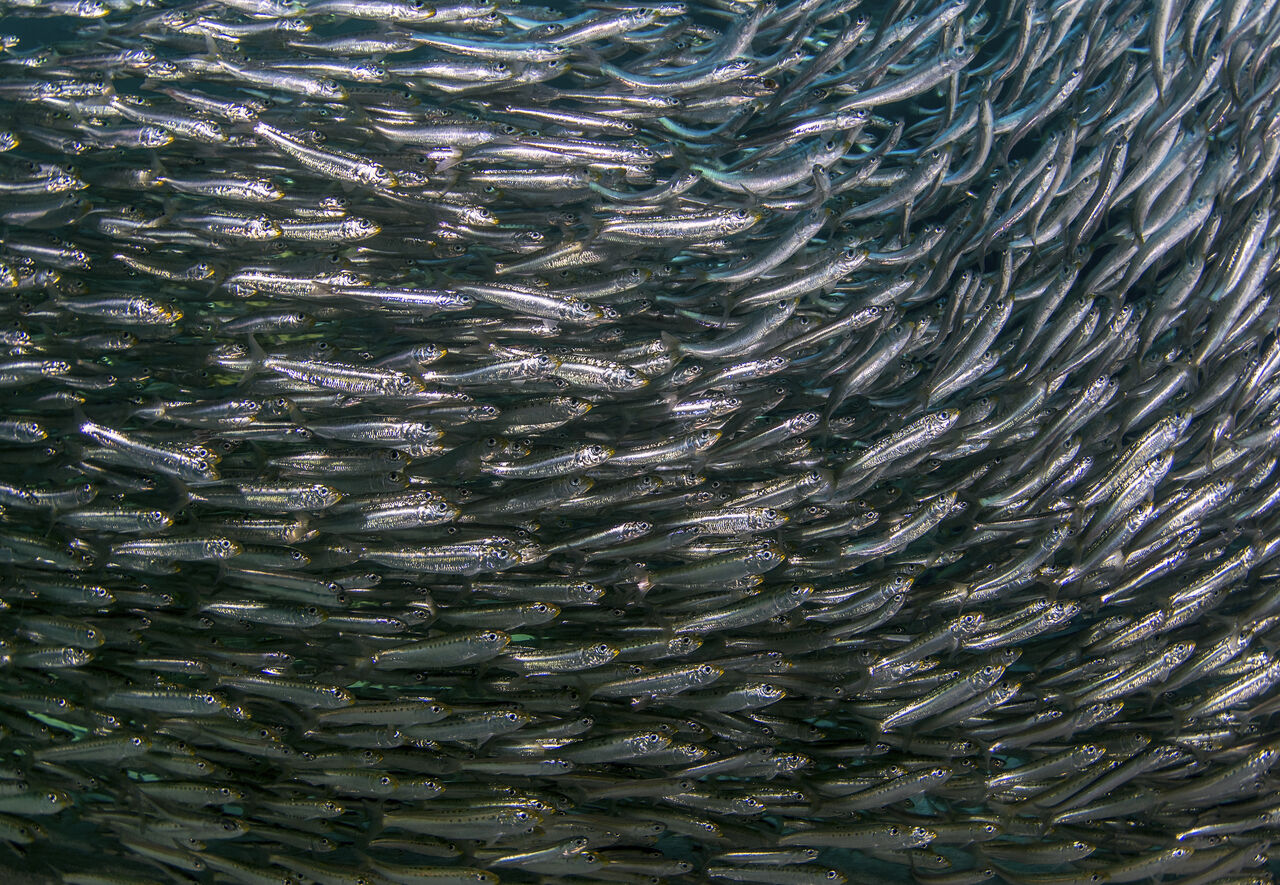

The sardine run is one of the ocean’s most extraordinary events. Every year, the ocean community flocks to South Africa’s east coast to witness this stunning display of abundance and biodiversity.

The sardine run takes place from mid-June to late July, attracting an incredible variety of marine life that feast on the sardines, like dolphins, whales, sharks, and seabirds. This natural phenomenon is often referred to as “the greatest shoal on Earth”, but the sardine populations have dramatically decreased over the past few years. This is largely due to competition with commercial fisheries and the impact of climate change.

What is the sardine run?

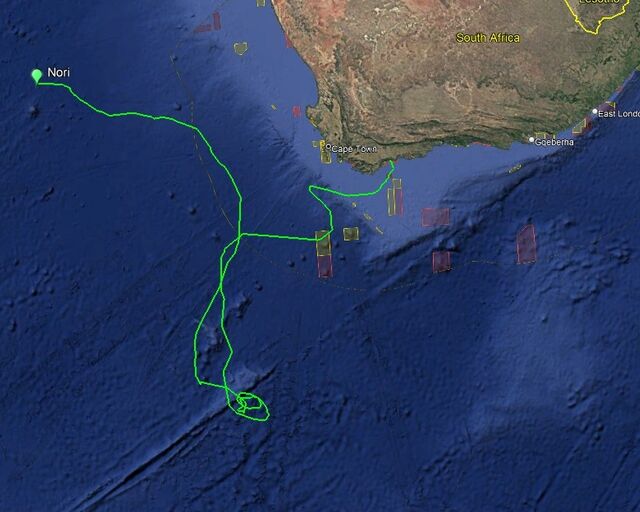

Every year, after spawning in Cape Agulhas, millions of sardines (Sardinops sagax) make their annual migration towards the Mozambican coastline in high-density shoals that can even be seen from space.

This epic journey is made possible by a seasonally unique ocean feature: During South Africa’s winter months, a cold counter-current flows northward alongside the warm Agulhas Current. This current is characterised by its proximity to the shoreline and its high rates of upwelling. Upwelling occurs when cold, nutrient-rich water comes to the surface, sparking phytoplankton blooms which attract large amounts of zooplankton. In turn, myriad marine life forms are drawn to the feeding frenzy.

The process of upwelling has a significant influence on the movement of the sardines. The west coast’s sardine population, drawn by the nutrients and colder water, follows the current northwards. As the sardines travel towards KwaZulu-Natal, they are penned in by the coastline of South Africa on their left and the warm Agulhas Current on their right.

During the migration, water temperatures may exceed the sardines’ typical range, leading to thermal stress and reduced health. Many scientists believe the sardine run is a throwback to a spawning behaviour dating back millions of years, when what is now the Indian Ocean may have been an important nursery area for the species.

Oddly, it appears that the sardine run is of little benefit to the sardines themselves, a fact which has long baffled scientists: KwaZulu-Natal’s waters are less nutrient-rich than those of the Cape, the favourable cool waters are only temporary, and the predation levels are heavy. But for the broader marine ecosystem, the sardine run is a critical event, holding the food web together.

Why are there fewer sardines?

Over the past several decades, it has become clear that the once vast migrations of spawning sardines have been fluctuating and slowly declining. There are two prevailing factors for the decline in sardine numbers: The pressures of commercial fishing and climate change.

Commercial fishing has decimated sardine stocks in South Africa and beyond.

Sardines are the backbone of global purse-seine fisheries. In fact, along with other small pelagic fish, sardines account for around a quarter of the world’s marine fish catch. In South Africa, they are harvested using purse-seine nets, with an estimated 200 000 tonnes of sardines caught annually in the Western Cape alone. This local industry, supplying food to fishmeal, supports the livelihoods of thousands of people. Unfortunately, this comes at a high cost.

Sardines are also the main prey source for a variety of predators, including other fish, marine mammals, and endangered seabirds. Essentially, this puts a significant portion of marine life in direct competition with commercial fisheries.

While sardine populations naturally fluctuate, recent years have suggested a downward trend. Furthermore, when sardine numbers are high (such as during the sardine run), they are more heavily fished and demand increases. This results in the low periods lasting even longer, shrinking the sardines’ usual range.

Climate change is visibly affecting the marine environment in real time.

Over 60 years of studying the sardine run, it has been proven that the first arrival of sardines off Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, has been delayed by an average of 1.3 days per decade. This links to the southward shift of the 21°C isotherm – the ocean’s thermal boundary that the sardines need to survive in their annual migration.

Once thrumming with life, the sardine run’s biomass had dropped to less than a quarter of its 2002 high. According to WWF’s Southern African Sustainable Seafood Initiative, sardine stocks are considered fully exploited, with concerns for the lower-than-average levels of biomass over the last 10 years.

Where the sardine run was once a spectacular mass migration, climate change has caused it to become increasingly fragmented as ocean conditions are no longer as favourable.

How do sardine numbers affect other marine species?

There are many marine animals whose species’ health is affected by the sardine run.

African penguins rely on sardines and other pelagic fish as a food source. With purse-seine fisheries depleting fish stocks, penguins are forced to hunt further afield, leaving their vulnerable chicks for longer periods.

Humpback whales travel from the Southern Ocean annually to our coastline’s feeding and breeding grounds. Unfortunately, there are fewer and fewer sardines for marine megafauna like whales to prey on.

The sardine run has long thrilled the ocean community for its abundant displays of marine life. However, its decline is a sobering reflection of the state of our ocean. Protecting sardines means preserving the ecosystems and livelihoods that depend on them.

Related News

Sign up to our Newsletter

Receive monthly news, online courses and conservation programmes.