Green turtles were downlisted on the IUCN Red List: Why conservation must continue

In October 2025, the green turtle’s (Chelonia mydas) global conservation status was changed on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN)’s Red List from Endangered to Least Concern. This is a significant success for one of the ocean’s most iconic species, and it is a result of decades of tireless conservation work around the world.

Green turtles were once in decline due to overharvesting for their meat, shells, and eggs, as well as global loss of nesting beaches and accidental capture in fishing gear. Their improved Red List status reflects an incredible, persistent show of coordinated global action, from international trade bans and community-led nest protection to more turtle-friendly fishing practices.

Green turtles inhabit the world’s tropical and subtropical oceans, grouped into 11 populations based on their distribution and breeding grounds. Some populations in areas where conservation efforts have been ongoing for decades, like the Southwestern Indian Ocean population around South Africa, have seen remarkable recovery. These successes have driven the global reassessment of the species’ status.

While the change in status is certainly cause for celebration, it’s also a reminder not to relax our efforts. The IUCN’s listing shows that conservation measures for key regional populations of green turtles have been working over the span of three generations. However, the fact remains that some regional populations, particularly in the central Pacific Ocean, remain threatened.

So, while the global trend is encouraging, the story is not a one-size-fits-all, and localised conservation remains critical.

Why this is cause for celebration and a warning

The purpose of the IUCN’s Red List is to highlight how likely a species is to go extinct in the near future.

Professor Ronel Nel, Associate Professor at Nelson Mandela University, explains that the list is a useful tool for comparing very different species by applying a standard set of criteria to assess the risk of extinction across species. For example, compared to African penguins, green turtles are currently doing relatively well.

“It’s a relative measure that says conservation for green turtles has worked. But, if we stop protecting them, we will go back to endangered status,” said Professor Nel.

It is critical to remember that all seven species of turtle are conservation dependent. Loggerhead, leatherback, and olive ridley turtles are all listed as Vulnerable, while hawksbill and Kemp’s ridley turtles are Critically Endangered. Flatback turtles’ status as Data Deficient is currently under review – previously, the lack of research into their abundance made it impossible to determine their risk level. So, each of the turtle species requires a sustained state of protection to maintain stable populations. If we want green turtles’ conservation status to remain of Least Concern, global conservation efforts must persist.

Turtles will always need conservation support. The odds are against them from their early years – only one or two in every thousand reach breeding age due to the high natural rate of hatchling mortality throughout their lives. To reach sexual maturity at 30 years of age, turtles must beat nature’s odds of predation and disease, as well as contend with the intense pressures of bycatch, habitat loss, and pollution.

Turtles’ highly migratory nature increases the probability of them encountering a greater range of threats as they move through multiple habitats. For example, the green turtles we see in South Africa were most likely born in islands in the middle of the Mozambique Channel, like Europa or Juan de Nova, and Madagascar. With such a slow maturation rate and so many life challenges along the way, ongoing protection of sea turtles is absolutely critical to their survival.

In other words, a change in status does not mean that the threats to the green turtle have disappeared. Instead, it means that conservation efforts are working and need to be maintained for the future.

Where do we go from here?

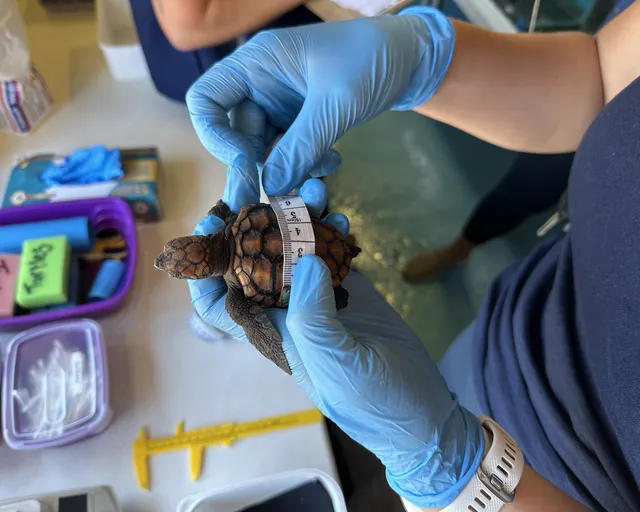

For the Two Oceans Aquarium Foundation’s Turtle Conservation Centre, this news is both motivating and grounding. The downlisting of the green turtle highlights that consistent conservation action, from beach patrols and bycatch mitigation to rescue and rehabilitation, truly makes a difference. Every turtle saved, rehabilitated, and released contributes to the broader recovery of this species.

Our work at the Turtle Conservation Centre plays a part in ensuring that this global success story continues locally. Many of our subadult green turtle patients bear the marks of human impact: Severe injuries from boat strikes, entanglement in ghost fishing gear, or the effects of plastic ingestion. These larger turtles require long-term care before they can return to the wild, and whether their recovery takes weeks or years, each release represents a second chance at life in the wild.

Before release, most of our turtles are fitted with satellite tags, allowing us to track their post-rehabilitation movements and contribute to a global database that helps scientists better understand turtle migration and survival. This data strengthens international conservation strategies, connecting our local efforts to the global mission of protecting turtles everywhere.

For green turtles like Bob and Bokkie, this second chance makes all the difference. Both turtles were rescued in dire condition – Bob, famously, excreted entire balloons and was declared “unreleasable” due to resulting neurological issues. Bokkie’s amputated flipper was the least of her problems when she later excreted 49 pieces of plastic. After successful rehabilitation (eight gruelling years in Bob’s case), both turtles were satellite tagged and released back into the wild.

Bokkie’s story had a sobering ending: After 150 days of being tracked, her satellite tag stopped transmitting. While there are several reasons why this may have happened, human impact is an alarming possibility. Injuries from boat strikes or accidental capture in fishing gear remain very real dangers. This is the hard truth the Turtle Conservation Centre faces with every release – after months or even years of care, each turtle returns to an ocean still shaped by human actions.

“The change in green turtles’ status actually makes me want to buckle down into the conservation efforts of the Turtle Conservation Centre even more! Conservation works, but stories like Bokkie’s remind us that turtles are always going to need it. So, let’s be encouraged to continue,” said Talitha Noble-Trull, Conservation Manager at the Turtle Conservation Centre.

The green turtle’s recovery is proof that coordinated conservation works, but also that these efforts can never cease. The challenge now is to keep this success story alive, one turtle at a time.

Related News

Sign up to our Newsletter

Receive monthly news, online courses and conservation programmes.